There is no proof in the record that “pressure” had an impact on a game’s result.

The 2015 World Cup semi-final loss to Australia, the 2017 Champions Trophy final loss to Pakistan, and the 2019 World Cup semi-final loss to New Zealand are just a few of the recent harrowing defeats the team has suffered in knockout encounters of international ODI competitions. Despite these defeats, some fans still think that the current Indian ODI team lacks the bravery and mental toughness needed to perform admirably under duress. But since these assertions are not supported by a thorough knowledge of the players and are not open to verification or testing, it is imperative to approach them with caution. These assertions lack empirical credibility and are essentially mind-reading.

Although the broad idea upon which such judgments are made – that a cricket match is composed of extended, insignificant periods with only occasional moments of intense terror and consequence, and that event or tournaments are comprised of unimportant fixtures and crucial ones – may seem absurd to readers, it still remains popular despite its logical difficulties. For instance, an ODI match consists of as many as 600 equally significant events called deliveries, with the outcome of each delivery influencing the final result, which depends on the cumulative outcomes of these deliveries. Teams strive to reach a conclusion as quickly as possible, which is evident from the fact that in ODI fixtures in this century, the average successful chasing team has won with 55 balls remaining, and 87% of ODI chases are concluded with at least one over remaining.

Effective target defense

The majority of ODI chases that are effective are finished with at least 32 balls remaining. The winning margin for teams that successfully make goals is 74 runs on average. Most effective target defenses are finished with at least 63 passes remaining, and 91% are finished with at least ten runs remaining. In ODI cricket, thrilling finishes to games are not the standard. Teams fight every ball because they want to gain as much ground as possible as soon as possible.

However, it would need to be explained if there was data in the past that indicated a squad consistently performed worse in some games than others. So the issue becomes, what are the various game types and how do teams fare in them? What is India’s current performance in them?

The Team IND is accused primarily of losing in “ICC knockout contests.” The evidence for this is based on a small number of games played over the last eight years, specifically the three ODI games noted in the first paragraph and a comparable number of World Cup games in T20Is. This depressing roster also includes the World Test Championship final. The structure is not particularly important. In the eyes of the public, “pressure” appears to determine these once-in-a-blue-moon fixtures fatally.

Since the 2015 World Cup began, IND has participated in 154 One-Day Internationals. Some claim that nothing in the other 151 games can make up for the results of the three previous matches because they show so much about the traits of Indian teams from this time period (a similar proportion of T20I and Test fixtures exists). This talk does not apply to those who hold this viewpoint.

But a classification can be based on the ICC knockout contests. Generally speaking, there are two kinds of matches in any series or tournament:

- Games contested prior to the series’ conclusion (live rubbers)

- Games contested following the conclusion of a series (dead rubbers)

There are two kinds of live rubbers:

A1. A squad can lose a game and still have a chance to win the series or tournament. Let’s designate these games that “can lose” CL games.

A squad must win games to remain in the running for the series or tournament championship. These games should be referred to as “MW contests” or “must wins.”

There are two types of dead rubber:

B1. Matches that are played after IND has already secured a series victory are referred to as “Series Won” (SW) matches.

B2. Matches that are played after IND has already lost a series, which are called Series Lost (SL) matches,

Since 2015, The team has played 15 matches against teams such as Zimbabwe, Ireland, Afghanistan, or an Associate Member team, winning 14 and tying one. These teams could be categorized as “weak opposition,” teams that IND expects to beat without any significant challenge. None of these matches were MW matches, but a few were dead rubbers. Out of the 14 victories, six were live rubbers against Zimbabwe in the CL category, and three were SW dead rubbers. In the World Cup and Asia Cup, IND played against Hong Kong, the UAE, Ireland, Afghanistan, and Zimbabwe a total of six times, winning five and tying once (against Afghanistan).

Even if they take place after a team has already qualified, league games in a World Cup or Asia Cup are not regarded as “dead rubbers” because the outcome of those games may still have an impact on the team’s qualifying spot.

The team should win MW games at roughly the same rate as they do CL games, barring the influence of duress. In other words, the win rate in MW matches and CL matches should converge as the number of such games rises. Dead rubbers are a distinct story because both teams may rest players during those contests.

India’s game record

Since the beginning of the 2015 World Cup, IND has played a total of 154 ODIs, winning 100 and losing 47. Out of these matches, 35 have been MW fixtures, and they has won 22 while losing 13. Regarding the 97 CL fixtures, IND has won 63 and lost 27. However, 12 of these matches (and 11 wins) were against weak opposition, which India is expected to beat with ease. If we exclude these matches, IND has won 52 and lost 27 out of 85 CL matches. India’s win rate in MW fixtures is 63% (22 out of 35), while their win rate in CL fixtures is 61% (52 out of 85), not considering no-results and ties. Ignoring these,

India wins 1.7 matches per defeat in MW fixtures and 1.9 matches per defeat in CL fixtures.

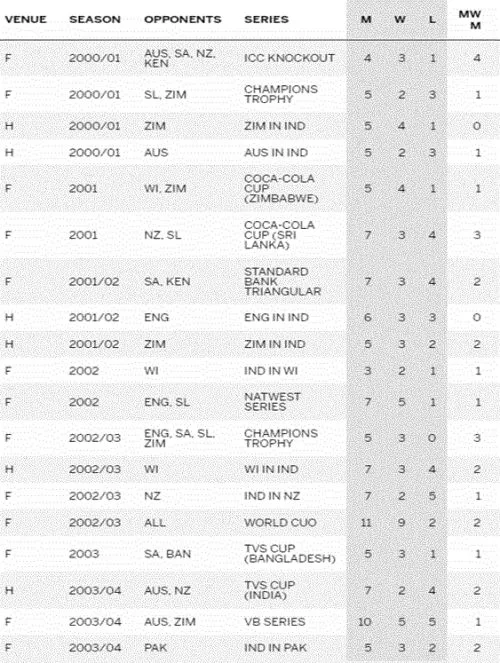

Taking the Sourav Ganguly era as a second example, it started with the ICC Knockout tournament in Nairobi at the beginning of the 2000-01 season and concluded with the Videocon Triangular Event at the end of the 2005 season. Similar to the Kohli era, the Ganguly era has produced many storylines. During Ganguly’s captaincy, India won one final and lost ten (and tied for one title in 2002 after two rained-out finals in Sri Lanka). Nonetheless, it is India’s victory in the 2002 final at Lord’s against a relatively weak English team that has become one of the iconic images of that era. In fact, a chapter in Ganguly’s memoir, A Century is Not Enough, is titled “Waving the Shirt at Lord’s.”

The point isn’t that the Ganguly era team performed worse in the championship game than in other games.For example, it was accepted wisdom back then that Sachin Tendulkar struggled in “crunching” contests. The problem is the arbitrary attribution of worth to a very small number of cricket matches, which is why these tropes, along with the notion that the Kohli-era team struggles in “big ICC knockout matches,” are all aspects of the same issue.

India played in 43 CL games under Ganguly, winning 50 of them. Their record in MW games was 19 victories and 18 losses. India played numerous games against inferior opposition during that time, including ten games against ICC associate member countries, nine of which India won. With the exception of the 2003 World Cup semifinal matchup against Kenya, these were usually CL matches. According to the data, India’s success record in MW and CL matches under Ganguly was comparable.

It could be claimed that winning MW games has, at best, been slightly harder for India than winning CL games. This slight difference in win rates can be attributed to the different opposition if you take into account that Tournament or competitions in which India is placed in must-win circumstances are apt to be more difficult than Tournament or competitions in which they are dominant.

Simply stated, the idea that a “big” competitive match is more difficult than the average, or “bilateral,” as it is frequently derisively called, is not supported by the evidence in the record. If there was such proof, it would indeed be extremely strange. The rules, the participants, and the surroundings all stay the same. Why should the success rate vary noticeably?

In summary, there is no indication in the record that “pressure” had an effect on how a fixture turned out. The relative caliber of both squads influences the outcomes. Teams competing in one-sided series are less evenly matched than teams competing in tournaments or event that enter must-win circumstances. An unreliable indicator of the character or caliber of a professional cricket squad is the occasional memorable final. A final is a competitive international match that its competitors want to win, just like any other ODI, T20I, or Test match we witness. Read more cricket updated here at IPLWin India.